By LENNY VANGILDER

Written for the LSWA

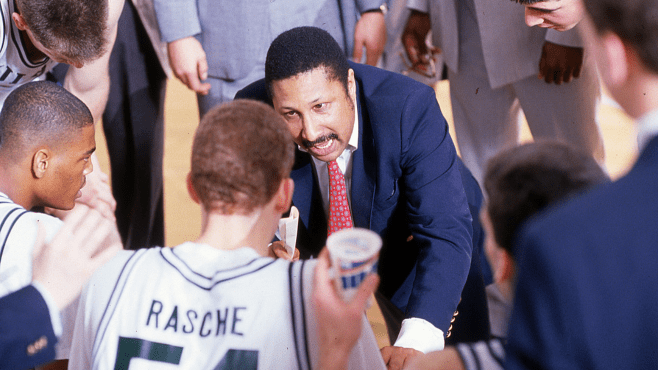

Perry Clark has often described his 11 seasons as head men’s basketball coach as Tulane University as his own Camelot.

But one of the great stories of college basketball in the 1990s didn’t exactly start out that way.

Shortly after Clark was hired in July 1988 to bring back the Green Wave program after a four-year, self-imposed shutdown, the coaching staff was set to host tryouts.

One significant thing was missing, however. No one had remembered to order basketballs.

It’s safe to say things got much better from there. Clark won 185 games in 11 seasons, taking Tulane to its only three NCAA Tournament appearances in school history, seven total trips to the postseason, and one conference and three division championships.

It is that remarkable rise from the ashes that has landed Clark in the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame’s Class of 2024. He is among a dozen state sports greats to be honored June 20-22 in Natchitoches. For participation opportunities, visit LaSportsHall.com or call 318-238-4255.

While Clark’s time at Tulane may have indeed been Camelot, it was also unique in so many ways.

What team has gone from no program to winning a conference title and reaching the NCAA Tournament in three seasons? Or at a university that had never even been to the NCAAs before, or since? Or using a 10-man rotation that featured an entirely new team coming onto the floor five minutes into the game?

“One through five, there are a lot of teams that might be better,” Clark would say on more than one occasion during the breakthrough 1991-92 season. “But one through 10, we can play with just about anybody.”

Clark, who played Division III basketball at Gettysburg (Pa.) College, had been a winner at every stop in his career. He was an assistant at his alma mater, DeMatha Catholic, under legendary head coach Morgan Wootten, where the Stags lost a total of eight games in three years.

As an assistant at Penn State, the Nittany Lions had three winning seasons and reached the NIT. Then in six years on Bobby Cremins’ staff at Georgia Tech, the Yellow Jackets won 123 games and made four trips to the NCAA, including an Elite Eight.

“I knew I hated losing,” Clark said in 1991, “and I wasn’t going to be (at Tulane) for four years and still be talking about building.”

Early on, Clark and his staff — which included eight future college head coaches during his time at Tulane — looked for something a little different. “What we really tried to do was get the best defensive player (in the Metro Conference) at every position,” Clark said.

After a 4-24 season in his first campaign with eight of the 11 roster spots occupied by freshmen, Tulane added another solid recruiting class and jumped all the way to 15-13 in year two. From 1974-91, only six teams went from a season of 24 or more losses to a winning record the next year.

Early that second season, Clark began using freshmen Carlin Hartman, Kim Lewis and Makeba Perry and senior Michael Christian together off the bench for the initial iteration of what would become college basketball’s most famous bench, “The Posse.” (Clark took the name from the popular wide receiver group of the 1980s of the NFL team in his hometown of Washington.)

“It evolved in the fall of 1990,” said Hartman, now associate head coach at the University of Florida. “(Clark) had a pretty good top five, but he had a talented group of freshmen that he and the staff wanted to get on the floor. He used (Christian, the team’s second-leading scorer in 1989-90) to be the captain of the second unit.”

The best, however, was yet to come.

Tulane got through the pre-conference phase of the 1991-92 season with eight consecutive victories and was one of 10 Division I teams still unbeaten as the calendar turned to January. All of them were ranked — except for Clark’s team.

The Green Wave opened conference play on a Saturday afternoon against Louisville, the longtime gold standard in the Metro. Tulane had one win in its history over the Cardinals, none in Freedom Hall.

The second version of “The Posse” — now a five-man wave who would enter around the first media timeout and immediately step up the tempo with its defensive pressure — featured Hartman, Lewis, Perry and newcomers Pointer Williams and Matt Greene.

“The Posse” combined for 59 points, including 21 from Greene and 20 by Lewis, as Tulane prevailed 87-83 in overtime.

Less than 48 hours later, the 9-0 Green Wave was ranked nationally for the first time since the 1950s. And from there, the story would grow by leaps and bounds.

Over the next eight weeks, just about every major network and newspaper was either on the phone or on their way to Tulane to tell the story of this unprecedented relaunch of a program and its uniquely structured roster, where the bench was more popular than the starters.

“(Clark) was really good at letting us go to a certain point,” said Hartman. “Then he would pull us back. Practice was really intense, but we had to play games. The starters felt like they were the reason we were having success, but we felt like we had the best bench in the country.”

The story kept growing. The winning streak reached 13, the second-best start in program history, before Tulane finally lost at Texas Tech. A 99-75 victory over Temple one week later was the most points ever scored against a team coached by the legendary John Chaney.

A first-ever ESPN appearance — in a time where landing on national TV was still rare — at home against Southern Miss introduced America to “The Posse.”

Even a late-season five-game losing streak couldn’t keep this Cinderella story from a happy ending.

Tulane won the Metro regular-season title on the final day of the season, defeating Southern Miss in Hattiesburg, and eight days later — while the team sat on the plane awaiting takeoff from a tough one-point loss in the Metro tournament final — CBS unveiled the NCAA Tournament bracket with Tulane’s name on it for the first time ever.

Clark’s team was a No. 10 seed in the Southeast Region, and he returned to his old stomping grounds, Atlanta, to face a St. John’s team under retiring head coach Lou Carnesecca.

A late jump shot by junior Anthony Reed — the first player to commit to Clark three years earlier — clinched a 61-57 victory.

The rapid ascent had not only made headlines, but earned Clark his second straight Metro coach of the year award and national coach of the year honors from the U.S. Basketball Writers Association and United Press International.

With only two departing seniors, Tulane started the 1992-93 season in the preseason polls. A gruesome leg injury to Lewis in the second game of the season would slow the roll, but the Green Wave would end up matching the 22-9 mark of the previous year with a return trip to the NCAAs, defeating Kansas State in the opening round.

The high point of the year came in the regular season finale against South Florida. The players who helped bring the Green Wave program back to life four years ago were honored on their senior day, and Reed — on his final shot attempt at home and a couple of hours after having his jersey No. 55 retired — drained a short jumper to become Tulane’s career scoring leader. He finished his four years Uptown with 1,896 points.

Tulane’s rapid rise opened doors for Clark and his staff to land higher-caliber players, and they didn’t have to leave the state to sign two big recruits in 1993: Jerald Honeycutt of Grambling and Rayshard Allen of Marrero.

Honeycutt and Allen, along with other highly ranked recruits Chris Cameron and Correy Childs, would reach the postseason in each of their four seasons. As sophomores in 1995, they got to the NCAA Tournament and defeated Brigham Young in the opening round, and a year later, despite a Conference USA division title and an 18-9 record, they were snubbed by the NCAA committee but quickly rebounded to reach the NIT semifinals.

Honeycutt would pass Reed and become Tulane’s career scoring leader with 2,209 points; Allen finished his career sixth all-time with 1,505 points.

“(The first four years) set the standard,” Honeycutt said in 2018. “Those guys paved the way. Even though we had some postseason success, (Tulane) is still known more for what those guys did before us.”

Before the NBA returned to New Orleans, 3,600-seat Fogelman Arena was as tough a place for opponents as any facility in the country in the 1990s. The interest in the program, however, warranted taking key games downtown for several years, first to the Superdome and eventually to the newly built arena known now as Smoothie King Center.

In one of those trips downtown in 1995, Honeycutt delivered one of the magical moments of Clark’s career, recovering a loose ball in the corner and hitting an acrobatic 3-pointer at the buzzer to defeat Florida State. It earned Honeycutt an ESPY award for Play of the Year.

“The minute that video comes on,” Honeycutt said, “it’s like a time machine takes you back to the Superdome.”

After two subpar seasons, Clark got Tulane back to the NIT in 2000, the program’s seventh postseason appearance in nine years. Three months later, he would depart New Orleans to become the head coach at the University of Miami. He spent four years with the Hurricanes and later was head coach for another four seasons at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi.

None of those will top the 11 seasons spent at Tulane.

“Through it all,” Clark said, “it was just a magical time.”

To put in perspective the remarkable decade-plus run that Clark, his staff and players assembled, Tulane, which made only two NIT appearances before the 1985 shutdown, has not been to either the NCAA or NIT since.

Though Camelot may have come to an end, the memories remain, three decades later.

Lenny Vangilder, a Tulane alumnus and former Green Wave sports information director, is a former LSWA president who is a writer/broadcaster for CrescentCitySports.com.