Written for the LSWA

Nobody could have seen what the future held when the first-time NFL head coach took the quarterback with still-fresh surgical scars on his throwing shoulder on a free-agent tour through a leveled city.

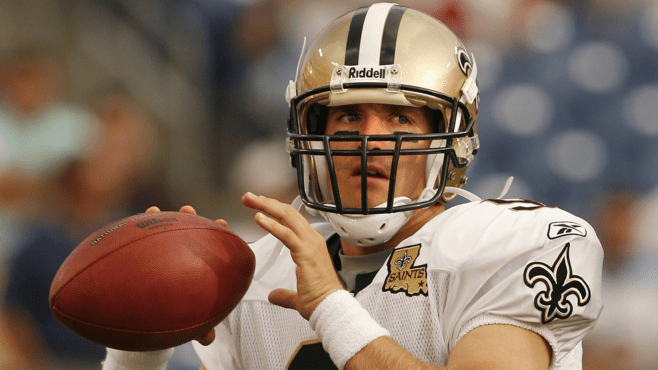

The three main characters in this story all needed someone to bet upon them. Coach Sean Payton was an unproven commodity taking over a franchise that had gone 3-13 the previous year and had just one playoff victory in its ignominious history. New Orleans was still reeling from the catastrophe wrought by Hurricane Katrina. And the quarterback, Drew Brees, was seeking a new home after suffering a devastating injury a few months before his free agent visit.

Payton was in the driver’s seat. He’d tried his best to hide the worst of Katrina’s destruction, but he was new to the city himself. After giving the Brees family a tour of the northshore of Lake Pontchartrain, Payton took a wrong turn down a road that turned into a dead end when the street was blocked by a tugboat.

Who sitting amid the wreckage would have pictured what would unfold — that Brees would become one of the most prolific passers in NFL history, and that the full measure of his importance would go far beyond the sheer weight of the numbers he accumulated on the field?

That initial pact Brees signed with the Saints and the city of New Orleans immortalized him in South Louisiana — the $60 million deal being repaid many times over. Brees is not only arguably the greatest free agent signing in NFL history because of what he did on game days, but also because of the role he played in getting a city and its people to heal and believe in what was possible.

Brees will soon be a Pro Football Hall of Famer, of that there is no doubt. First, he will take his rightful place among the greatest sports icons in the state’s history when he is enshrined June 22 in the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. He is part of the 12-member Class of 2024 to be honored June 20-22 in Natchitoches. For participation opportunities, visit LaSportsHall.com or call 318-238-4255.

His playing career spanned 20 NFL seasons, the last 15 of which were spent leading the Saints. He played a critical role in reversing the fortunes of the Saints franchise at a time when the city and region needed it most, leading the Saints to their first conference championship appearance in his first season, and a Super Bowl title in his fourth.

“When I was hired by the Saints as head coach in 2006, the very first goal was to establish a functional and winning culture,” Payton said after Brees’ retirement. “In doing so, it was vital to know what we were looking for in a player. Talent, work ethic, makeup, intelligence and leadership are all qualities we found in Drew Brees. We also found a player with a burning desire to win.”

Those traits fueled a football legacy that is almost unrivaled. At his peak, Brees reached previously unknown heights, and because his peak spanned what would amount to an entire career for many accomplished football players, Brees’ career towers even above the greats.

At the nexus of skill, intelligence and focus, there was Brees, beating the world’s premier athletes and defensive minds not only because he had the talent, but because he was so thoroughly prepared he seemed to know where they all were going better than they knew it themselves.

He was a football supercomputer, processing in real time and at breakneck speed what is difficult for most to decipher with the benefit of high-resolution, slow-motion instant replay. Brees did not come upon this trait by chance. His work ethic is the stuff of legend.

Brees famously embodied the “first one in, last one out” ethos that belongs to the greats.

His former teammate, Jeremy Shockey, once said about Brees’ early arrivals to the Saints

practice facility, “I cannot beat him here.”

His constant excellence was rooted in that meticulous and grueling preparation. No details were too small, no stone left unturned. While Payton was constantly pushing against the idea that Brees was not a tremendous athlete, it was this combination of brain and ability that made him transcendent.

When Brees formally announced his retirement in 2021 — 15 years to the day after he signed with the Saints — he was the NFL’s all-time career leader in passing yards (80,358) and completion percentage (67.7). His 571 career passing touchdowns ranked second all time.

Brees led the NFL in passing seven times in his first 11 seasons in New Orleans. During one five-season stretch, he led the league in touchdown passes four times. He currently owns six of the nine best single-season completion percentages in NFL history. And for a player who came to New Orleans with durability concerns, he missed only one start because of injury in his first 13 seasons with the Saints.

Taken as a whole, his career is hard to wrap one’s mind around. Brees and the Saints offense routinely shattered NFL norms, trailblazing a path for the high-flying modern offenses of today. Sprinkled throughout that long period of excellence were some of the single best performances in NFL history.

There was the Monday night in 2009 against the Patriots, when he fired as many touchdown passes (five) as incompletions on his way to a perfect 158.3 passer rating.

There was the 2015 barnburner against the Giants, when he became the second player in NFL history to record 500 yards passing and seven touchdown passes in a single game — joining another native Texan who went on to star in the boot, 1972 Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame enshrinee Y.A. Tittle, an LSU product.

There was the Monday night in 2019, when he broke New Orleans native and Louisiana Sports Hall of Famer Peyton Manning’s career record for touchdown passes against Manning’s old club, the Indianapolis Colts — and in the same night completed 29 of 30 attempts to break the NFL’s single-game completion percentage record. Tom Brady went on to break Brees’ career touchdown and yardage marks.

With Brees running the show, the Superdome became a nightmare for opposing teams, and Brees consistently saved his best for the home crowd.

There was 2011 — one of the greatest individual seasons by a quarterback in NFL history — when he threw an NFL record 29 touchdown passes in home games. There was the 2015 season, when he threw for a then-NFL record 2,853 yards in home games. There was the 2018 season, when he posted an NFL record 133.3 passer rating in home games. There was the 2019 season, when he completed an NFL single-season record 77.5% of his passes in home games.

He changed the dynamic between the city and its football team with his superior play. Brees helped author 151 wins as the Saints quarterback, including nine in the postseason, easing the suffering of a fan base that witnessed only 238 wins in the 39 seasons of franchise history before Brees arrived.

Before he became an NFL star in his own right, Tyrann Mathieu was a kid in New Orleans watching Brees perform his magic. Seeing Brees in a No. 9 Saints uniform gave him a feeling he didn’t know too often before: A chance to win every Sunday.

That feeling of thinking anything was possible reached new heights when Brees was named the MVP of Super Bowl XLIV, after throwing for 288 yards and two touchdowns in a 31-17 win against the Colts.

“He definitely brought a different attitude, a different spirit to the city,” Mathieu said after Brees’ retirement. “And I think when he brought that championship back home to New Orleans, that not only did that do a lot for him and the Saints organization, but I think everything that city had been through, we finally had a reason to celebrate.”

For all his overflowing ability that made him an icon, there is an everyman quality to Brees that makes up a substantial part of his legend. He is undersized by football standards; he was lightly recruited; he was doubted coming into the NFL; he was doubted again after leaving his first professional home, San Diego, after suffering a complete tear of his labrum in the regular-season finale.

Brees’ constant excellence was a quiet taunt to his naysayers. He overcame the doubts not just with his ability, but with his drive. As special and unique as that force is that made Brees great, it also makes him relatable. Even those with a fraction of Brees’ talent can try to emulate the fire inside.

And Brees’ reach extended far beyond the confines of the Superdome. He routinely leveraged his fame and his personal wealth to make New Orleans a better place.

Whether the scale was relatively small — like funding a new weight room for Lusher Charter School in the wake of Hurricane Katrina — or gargantuan — like his $5 million pledge to deliver food to people in need during the coronavirus pandemic — the Brees family’s philanthropic work directly impacted the lives of thousands in Louisiana.

Brees came to Louisiana in some ways a broken man, with an unproven, surgically repaired throwing shoulder that had him struggling to even lift his uniform in his introductory press conference. He needed someone to bet on him. The place he found was in some ways broken, too, a floundering franchise in a city that felt abandoned over and over again, always in the midst of putting itself back together. New Orleans needed someone to bet on it, too.

Who in their right mind could’ve seen all this coming when Brees first toured New Orleans back in 2006?

Maybe it took someone with vision and focus, and the determination and skill to see it through.

In a televised interview shortly after winning the Super Bowl, this was how Brees described the moment.

“Just feeling like it was all meant to be. It’s all destiny.”

Luke Johnson covers the Saints for the Times-Picayune | NOLA.com.

–LaSportsHall.com–