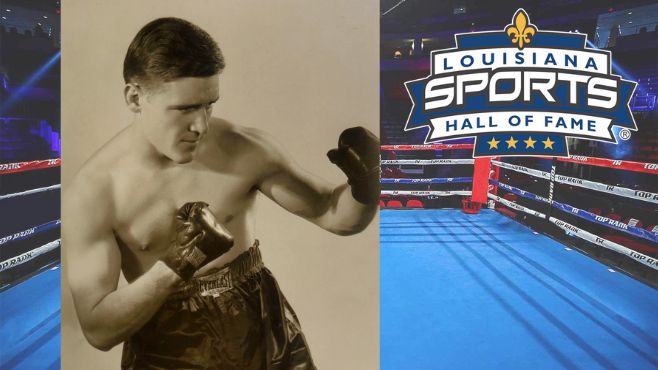

Eddie Flynn is generally regarded as the greatest amateur boxer in New Orleans history.

The pinnacle of his undefeated amateur career – which featured boxing at Loyola University under the tutelage of legendary Tad Gormley – was his gold-medal victory as a welterweight (147 pounds) at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Flynn’s boxing accomplishments have finally, 90 years later, earned him induction into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame where he joins his mentor.

Flynn’s career will be celebrated June 23-25 in Natchitoches as he and 11 others are spotlighted in the Class of 2022. For participation opportunities and information, visit LaSportsHall.com or call 318-238-4255.

But the immortal acclaim of being an Olympic gold medalist was no more important to Flynn than another title he earned – Doctor.

Dr. Eddie Flynn was as accomplished as an oral surgeon in Tampa as he was a boxer before, during and after his graduation from Loyola in 1936. The two careers of Eddie Flynn, who posthumously will become the seventh boxer inducted to the Hall of Fame, reveal an enigma.

“He would never swear,” said Flynn’s grandson, Doug Belden, “but he would put the fear of God into you.”

Belden knows because he was largely raised by his grandfather after both of his parents died relatively young.

“He was my closest friend,” Belden said. “My grandfather basically took over my whole life (after the parents’ deaths). I knew from the time I was six or seven that he was a tremendous boxer and did win in the Olympics.”

Dr. Flynn’s accomplishments have resonated through subsequent generations.

“He was always a legend in the family,” said Cory Martin, Belden’s nephew, who will accept induction on his great-grandfather’s behalf in Natchitoches. “He stepped in as the father figure of the family. There has always been that lore.”

Martin said “it was a fantastic experience” while preparing to accept the induction as he “dove into research” about his great-grandfather’s boxing career and life.

It was quite a career and life.

The story of Dr. Flynn’s life, which touched countless lives in New Orleans and Tampa, actually began in the small town of Sapulpa, Oklahoma.

The Flynn family had emigrated from Ireland and Eddie’s father was a newspaper publisher who ran afoul of the Ku Klu Klan when Eddie was a youngster because of the family’s heritage and editorials the paper had published denouncing the Klan’s practices.

“They gave his family 48 hours to leave town,” Belden said. “So they migrated from Oklahoma to New Orleans.”

The family later relocated to Tampa before Eddie returned to New Orleans to attend Loyola on a boxing scholarship.

Flynn started his boxing career in Florida, though he did so without telling his father, who he believed wouldn’t approve.

Belden said Flynn would “slip out of the house” to go box under an Irish alias – “McGregor or something like that.”

Eventually Flynn’s father discovered his son’s boxing career.

“He told my grandfather,” Belden said, “if you ever lose a bout as an amateur you’ll never put the gloves back on.”

The gloves stayed on for a total of 144 amateur bouts – 144 amateur victories.

The boxer believed his father would fear his son getting hurt and didn’t see any future in boxing.

But Flynn had a plan.

First his boxing skill paid for his education at Loyola, although he essentially repaid the athletic department.

“Basically he supported the entire athletic program at Loyola University because of his boxing abilities,” Belden said. “He’d fill up the gymnasium.”

Flynn won an AAU national championship in 1931, then came the Olympic year and he repeated as AAU champion, won an NCAA championship and made the U.S. national team.

According to the 1932 Loyola Wolf Yearbook, “(Flynn) was chosen to represent the United States in the welterweight division in a series of boxing matches in New York with the European champions from Italy.” Flynn defeated the Italian champion, who held the “crown of the foreign countries.”

In each of Flynn’s Olympic bouts he knocked his opponent down in the first round and went on to win on points.

“I believe in his heart he knew if he had to, he could knock the person out or knock them down every round,” Belden said, “but he was such a clever boxer (that he didn’t have to).”

The welterweight division was the most crowded at the Games, featuring 16 boxers. Flynn won three matches to reach the gold-medal bout, his fourth fight in five days, against a German policeman named Erich Campe, winning a three-round decision, 60-59.

All nine of the Flynn brothers boxed while growing up, earning the group the nickname “The Fighting Flynns.”

One of Eddie’s brothers, Dennis, was a teammate of his at Loyola and won a silver medal as a middleweight at the ’32 Games.

One of Flynn’s other U.S. teammates did win gold as the pair produced the last Olympic gold medals won by Americans until the U.S. won five at the 1952 Helsinki Games.

Flynn turned professional after the Olympics. There are conflicting reports about his precise professional record. It was might have been 23-7-1, 29-7-2 or 14-1, but the primary purpose of the professional career was to finance his way through dental school and to start his own practice.

He was drafted into the military in 1935 and served through the end of World War II.

According to www.NBCOlympics.com, Flynn explained his relatively short professional career by saying, “I got kind of sick of putting on gloves and hitting some fellow in the face when I’ve got nothing against him.”

Belden told a story that demonstrated his grandfather’s attitude toward his opponents. Dr. Flynn and his wife, Olive, would spend the month of October in Europe each year.

One October, many years after the Olympics, Dr. Flynn managed to track down Campe, the fighter he had defeated for the 1932 gold medal, in Heidelberg, Germany.

“They became great friends and were pen pals for many years,” Belden said.

Although Flynn always stayed “in phenomenal shape,” his post-boxing life was spent in ways that might seem inconsistent with the most common characteristics of a world-class pugilist.

“He was always real big on manners – ‘yes, ma’am, no, sir,’” Belden said “He had very, very old-fashioned, Irish manners. He was an avid reader. He was big into growing azaleas. He had a big heart for people. He wasn’t a bully. Very unique.

“He told me one time, ‘Son, violence is horrible. Rather than knocking people out I’d rather be helping people. Son, it’s never about net worth. It’s about self worth.’”

Flynn, who served as Florida boxing commissioner for a while after retiring, would bring his grandson with him to bouts. At one bout that the pair attended, he was introduced to the crowd as Olympic Gold Medalist Dr. Ed Flynn.

At his request, that was the last time he was ever introduced at a match.

“He didn’t like standing, he didn’t like notoriety,” Belden said.

But notoriety naturally came to him.

Flynn’s boxing exploits earned him induction in the Loyola Athletics Hall of Fame as part of the inaugural class in May 1964, induction into the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame in 1981, the Florida Sports Hall of Fame in 1974 and the Florida Boxing Hall of Fame in 2010.

Additionally, Belden donated his grandfather’s Olympic gold medal and the boxing gloves he used in the Olympics for display in the Tampa History Museum, which also features a video of a conversation between grandfather and grandson.

But the end of Eddie Flynn’s boxing career was just the beginning of his professional life.

“As an oral surgeon he would take care of all the poor people, the nuns, the priests, the police officers, the firemen,” Belden said.

Dr. Flynn would tell those patients, “pay me what you can.”

Belden said Dr. Flynn taught him “the importance of getting along with people from all walks of life.”

“He was a really personable guy,” Belden said. “Everyone in community knew him and he served the community.”

Dr. Flynn would drive around various Tampa communities in his distinctive Volkswagen “Bug” that was green in honor of his family’s homeland. His personalized license plate read, “Amigo.”

“They wanted him to run for mayor of Tampa,” Belden recalled, “but my grandmother said ‘absolutely not.’”

Dr. Flynn’s grandson used the political skills he learned from his grandfather to get elected county tax collector in 1998 and he was continually re-elected, unopposed, until retiring last year.

Belden made it a point to get to know his constituents “from the bottom to the top” throughout “the Hispanic community, the African-American community, the Caucasian community, the Asian community.”

“I learned every bit of that from Ed Flynn,” Belden said.

If dentistry halls of fame were as commonplace as sports halls of fame, the list of inductions for Dr. Flynn would be even longer than it is.

“He said he did not enjoy hurting people,” Belden said. “He didn’t really enjoy the sport, but he felt he was a natural. I believe that’s why he went from that extreme to be an oral surgeon and taking care of people’s teeth at no cost or very little.

“He went from inflicting pain to relieving people’s pain.”

Written for LSWA by Les East.