Story written by Jason Pugh for Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame

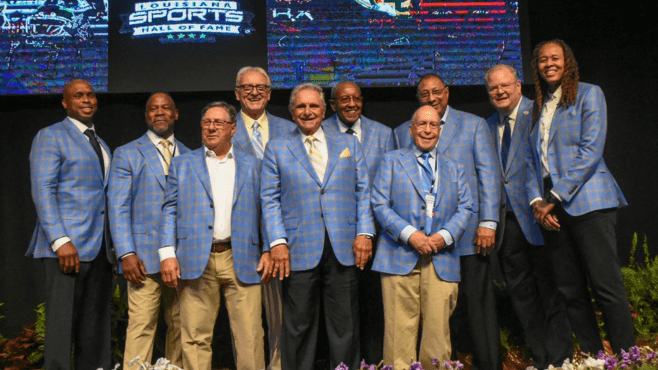

NATCHITOCHES – The 12 members of the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame Class of 2024 brought worldwide acclaim to their home state – adopted or natural.

Fittingly, two of the newest Hall of Famers brought the world to Natchitoches.

Although New Orleans Saints Super Bowl-winning quarterback Drew Brees and former UFC champion Daniel Cormier joined the proceedings via video from Japan and Saudi Arabia, respectively, the stories of the 12 inductees started much closer to home – specifically within their homes.

“I had the greatest parents,” Distinguished Service Award in Sports Journalism honoree Bobby Ardoin said tears, “because they didn’t have to adopt me, and they did. They let me do just about anything I wanted. I wasn’t always a summer’s breeze, but they’re the reason I’m here today.”

That reasoning resonated throughout the eight competitive-ballot inductees and the four award winners who officially joined the state’s athletic shrine during the three-plus-hour ceremony at the Natchitoches Events Center.

The inductees’ praise did not stop at biological family members.

“I had some of the greatest parents in the world, and I have some of the greatest people in the world here tonight,” longtime Grambling baseball coach and the second Louisiana Sports Ambassador Award honoree Wilbert Ellis said. “I always wanted to give back. I always wanted to make a difference. That was my prayer. God gave me that prayer, and I’ve been all over the country doing it.”

The prayers of long-suffering New Orleans Saints fans officially were answered in January 2010 when Brees led the franchise to its lone Super Bowl title, but the seeds were laid four years earlier when he signed with the franchise.

“The Saints thought they had a quarterback,” said Brees’ teammate Steve Gleason. “They didn’t realize they hired Clark Kent.”

Brees and the city bonded over their respective recoveries – Brees from a shoulder injury and New Orleans from the effects of Hurricane Katrina – to build a relationship that became like family.

The record-setting quarterback from Texas who played collegiately at Purdue in West Lafayette, Indiana, and his home city became inextricably linked – a bond that continues today.

“It’s funny how life works out,” Brees said in a video that was played during the ceremony. “I never had any exposure with New Orleans. I didn’t know much about it. To think of the sequence of events to where I could play for the Saints, I could not imagine a better place to play football or a better fan base to play in front of. There was a college atmosphere of the fans being so invested in the team. They’re a part of the fabric of the community, and you feel it quickly. The connection between our team and the Who Dat Nation is the example for professional teams across the world as for how a team can be that integrated in the community.”

Roughly an hour west on Interstate 10, the Baton Rouge community saw one of its most notable, successful products honored Saturday night.

LSU All-American Seimone Augustus spent her high school career at Capitol being feted as the nation’s No. 1 player. In an era where Tennessee and UConn “had a chokehold on the recruiting game,” according to Augustus, she made the decision to stay home and build something.

That something included the start of five straight Final Four runs for her hometown university and a sweep of the 2006 National Player of the Year honors.

“I was never a trend follower,” Augustus said. “I was a trendsetter. A lot of players as soon as they got a letter from Connecticut or Tennessee, they committed. I was like, ‘Don’t you want to take a visit?’ ‘Don’t you want to meet your teammates?’ I begged to differ. When I didn’t go to Tennessee or Connecticut, a lot of people thought I was crazy. Coach (Sue) Gunter, coach (Pokey) Chatman, coach (Bob) Starkey, they were sending me handwritten letters from when I was eight or nine years old.

“I went through every recruiting letter. Some were authentic. Some you could change my name for someone else’s, and it read the same. LSU’s authenticity and the fact it was in my backyard and the chance to build something that had not been build before (were factors). I could go somewhere else and be one of the greats, or I could be THE great. That was my thought process.”

Staying at home to build the program she grew up watching appealed to Augustus, whose initial impression on Starkey came in an athletic setting but not at an athletic event. It gave him insight into where the woman who now has a statue outside the Pete Maravich Assembly Center’s priorities laid.

“The very first time I saw her in person was Thanksgiving at the Riverside Centroplex (now the Raisin’ Cane’s River Center) and she was serving food to the less fortunate,” Starkey said. “Here’s the No. 1 high school player in the country, and she’s spending her Thanksgiving making others feel better.”

Those lessons began at home, forming both Augustus’ altruistic side and a work ethic that forced the LSU staff to adjust its practices.

“No one was going to outwork me,” Augustus said. “I learned that from watching my parents. Within my household, I was driven because I watched two people sacrifice so I could have. I wanted to work hard to give them something to be proud of.”

If anyone in the Class of 2024 could commiserate with Augustus regarding building a program, it is former Tulane men’s basketball coach Perry Clark.

When Clark arrived in Uptown in July 1988, the Green Wave program was in its infant stages of being resurrected following a self-imposed, four-year shutdown following a point-shaving scandal.

Within two seasons, Clark took Tulane from a resurrection point to the first – and still only – conference championship in program history.

“He had to restart a Division I men’s basketball program, and there was no blueprint for him to follow,” former Tulane sports information director Lenny Vangilder said. “From no program to two years later winning a conference title, it was truly remarkable and may never be done again in the history of college athletics.”

Clark did just that in his own way – focusing on what Tulane could have instead of what it didn’t.

“I knew we weren’t going to get the best offensive players,” he said. “We were able to build defensively. We had the best defensive player in the conference at each position. That first year, we upset Memphis State, who was ranked No. 4 because we were able to stop Elliott Perry. We had a top-20 win every year because we could lock in defensively and believe in what we were doing.”

Armed with a bench group nicknamed “The Posse” after Clark’s favorite NFL team – the then-Washington Redskins – and their dynamic receiving corps, the Green Wave had all three of its NCAA Tournament appearances in Clark’s 11 years at the place he called Camelot.

While Clark left his mark on Tulane, winning 185 games in those 11 seasons, it left just as much of an imprint on him.

“I’m very privileged to be in the state of Louisiana,” Clark said. “The people here have inspired me in my growth as a person, my growth as a coach. This is the most wonderful group of people in the country. You love with your heart. You give with dedication and care. We had to live up to your energy, your desires and the things you hold very, very special – loyalty and caring. If I ever get accused of being too loyal, I hope they find enough evidence to find me guilty.

“I kept asking how do I get in this Hall of Fame. I kept hearing, ‘It’s too hard. It’s too hard.’ I kept asking, ‘What do I have to do?’ This is extremely special to be called a Cajun. I’m happy to be here and happy to be recognized as a Cajun.”

There is no doubt Daniel Cormier is 100 percent Cajun.

The former wrestling standout who went 101-9 in his career at Lafayette’s Northside High School has carried the banner of his hometown and home state worldwide.

Unable to attend the ceremony because of a UFC broadcast assignment that took him to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Cormier extolled the virtues of Acadiana via video Saturday night.

“When you look at certain schools, you know what they have,” he said. “Northside did a great job of forming me – not just athletically. They helped me with my academics, which I struggled with initially. They taught me to be a better person. I had great coaches who made the biggest impacts on my life. Northside is the perfect high school for me. I can proudly say I was a Viking even now.”

Cormier, the first UFC fighter to simultaneously hold titles in two different weight classes, has become a mainstay on UFC broadcasts, something that did not shock those who knew him before his junior college career and his standout years at Oklahoma State.

“A lot of high school kids are on the shy side and don’t want to do interviews or answer questions,” said Acadiana Advocate writer Kevin Foote, a Lafayette sports journalism cornerstone. “Daniel Cormier was not like that.”

Instead, he showed early the type of attitude that carried him throughout a wrestling career that took him to the Olympics and into an MMA career that placed him smack in the middle of the rise of the sport’s popularity in the 2010s.

“It’s an honor to call him my friend,” said UFC ring announcer Bruce Buffer. “He always comes in with a smile on his face and leaves with a positive attitude. He is a role model personified.”

Cormier’s absence was about the only thing that kept induction weekend from being a perfect moment for Olympic gold medalist Kevin Jackson, who spent the first three years of his college career at LSU before the school dropped the sport.

Undeterred, Jackson made his final season count, captaining Iowa State’s national championship team while producing an individual national runner-up season.

“We were really fortunate at Iowa State to have him transfer in after being an All-American at LSU,” Cyclones coach Jim Gibbons said. “We had an interesting group of younger wrestlers and a group of older wrestlers who had underachieved to that point. Kevin bridged the gap between those two groups, and they both had success.”

While Jackson did not collect an individual national championship, he made up for it in 1992, capturing Olympic gold in Barcelona. His medal winning performance came just hours before the closing ceremonies, which is where Jackson said he had his Olympic moment.

“The closing ceremonies are very different than the opening ceremonies,” Jackson said. “During the closing ceremonies, there are still events going on and some after. The opening ceremonies, you’re walking in the stadium in a suite and tie. At the closing ceremonies, you’re sitting in the stands with the other Olympians and athletes watching them still competing. What I noticed was a jumper leaping over a high bar and a javelin going through the air, and I thought, ‘This is it. This is the Olympic games of Jesse Owens, Jim Thorpe, Muhammad Ali and Mary Lou Retton, and I’m now a part of history,’ There was an overwhelming sense of achievement, and I’m having that same feeling right now.”

Now an assistant coach at Michigan, Jackson had hoped to spend the weekend alongside Cormier, whom he coached during the latter’s Olympic appearances in 2004 and 2008.

“I love Daniel, and you could feel his energy and passion through the video,” Jackson said. “We are bonded in several ways. Part of this being special was going into it with Daniel. Unfortunately, he had to go overseas. Seeing him on screen and meeting everyone, it’s been a special weekend.”

Both Cormier and Jackson had remarkable winning percentages in individual sports, not different from jockey Ray Sibille, who grew up just north of Lafayette in Sunset.

When the sun finally faded on Sibille’s remarkable career that officially began on south Louisiana’s bush tracks – unofficially on the family farm – he had saddled more than 4,000 winners across the country, including a win in the 1988 Breeders’ Cup, adding to the legacy of Acadiana-bred jockeys.

“I remember them telling us, ‘You better come to school. You ain’t getting nowhere riding a horse,’” Ray’s brother Larry Sibille said. “He was going to be a jockey. Nothing was going to stop him.”

And little did – even when during a race between the Sibille brothers in their younger days ended with Ray’s horse running into a cow, leading to a restart of the race.

What started as a family affair led to Saturday night’s induction for Sibille as he followed his good friend, Eddie Delahoussaye, into the state’s shrine.

“We always had horses in the pasture,” Ray Sibille said. “My brothers, we’d catch them and race them. It was part of life that we did. We all loved it. I had two brothers that rode, Ronnie and Jimmy, who got killed. They both could be right here with me if it worked out for them like it did for me.”

Sibille found more kinship during his time in Natchitoches.

“The people I’ve met here – the athletes and the coaches – they were unbelievable,” he said. “On the way to Alexandria, I sat with coach Ellis and Frank Monica and Kerry Joseph, and we were sitting next to each other. Boy, we shared some war stories.”

Riding home winners and turning boys into young men marked Monica’s five-decade career in coaching.

The decorated Monica led a trio of south Louisiana schools – Riverside, Lutcher and St. Charles Catholic – to state football championships after a college baseball career at Nicholls where Monica was part of a national runner-up Colonels’ team.

Flip-flopping between high school and college coaching jobs, Monica stayed true to one constant – Louisiana.

“I had an opportunity to leave the state,” he said. “I decided to stay in the state. I made the right decision. I believe in Louisiana athletes and Louisiana football, especially in the River Parishes. If you don’t play football there, you don’t eat. It’s a good brand of football. They gamble on every ball game, so you better win.”

And win Monica did – not just on the field. His teachings left a lasting impression on his players, his staff and even opposing coaches.

Upon hearing coaches from Lutcher and East St. John praise Monica, host Victor Howell remarked on how impressive it was for Monica to draw praise from coaches of rival programs.

Monica quickly retorted, “That’s exactly how I wrote it.”

Said Wayne Stein, the coach who followed Monica at St. Charles Catholic: “The greatest influence on my career is Uncle Frankie. It wasn’t always easy. He’s an intense guy, but it’s something when you look back, you appreciate going through the struggles. All he ever wanted was for you to be your best.”

Kerry Joseph understands that.

The four-year starting quarterback at McNeese had his own version of Monica at home – two to be exact.

Following a recruiting visit to McNeese, Joseph had a visit scheduled for Northwestern State the next week. Joseph spoke with his father, who told him to go back in and accept the scholarship offer from head coach Bobby Keasler, a New Iberia native like Joseph.

“I listened to my dad, which is what happens when you get a lot of whippings,” Joseph said to a roomful of laughter. “It happens when your mom’s an educator and whips you also. It was the best decision I made.”

After a redshirt season in which Joseph contemplated leaving McNeese, he came in relief against Nicholls in Week 3 of his redshirt freshman season and led the Cowboys to a comeback victory. From Week 4 of that season until he left campus, Joseph never left the starting lineup.

The arm talent that wowed those who saw it – and frustrated at least one group of 12-year-old all-star baseball players – never left and helped McNeese reach the FCS semifinals and ascend to a No. 1 ranking during Joseph’s career.

As for those 12-year-olds, former Distinguished Service Award winner in Sports Journalism Glenn Quebedeaux had a front-row seat for it.

“I took that team to Iberia Parish to face them in a tournament,” he said. “When somebody strikes out 15 of your batters, you don’t forget it.”

While Joseph reminisced wistfully on his baseball career on stage, he took with him plenty of wisdom that had little to do with pumping mid-80s heaters past his overmatched peers.

“It’s amazing I had to come behind coach Ellis,” Joseph said. “It was a divine meeting to go in the class with these great athletes. We had a 50-minute ride to Alexandria and a 50-minute ride back, and you get to talk and soak in the wisdom with coach Frank Monica, Ray and coach Ellis. (Ellis) told me one thing, ‘Make sure you don’t forget the people who came to support you.’”

Virtually the entire town of Grambling seemed to be in the Natchitoches Events Center to honor Ellis, whose 43-year career at Grambling serves as a bridge between the Tigers’ present and its gilded past. While his current iteration has him traveling across the country as an NCAA Regional and Super Regional supervisor, his impact continues to be felt throughout Lincoln Parish.

“When you talk about impact, it’s bigger than baseball,” current GSU head coach Davin Pierre said. “He’s a man of honor and integrity. He’s iconic. You cherish those moments when you can be around him. With someone like him, you just sit down and listen to what he says and soak up all that knowledge. He’s been a great asset to me.”

Ellis is a spiritual man who often acknowledges God, and he did so Saturday night, reiterating a prayer request for him to stay involved in the game he loves once he stepped away from coaching.

“I asked God to keep me in the game of baseball, and He did,” Ellis said. “I met (longtime College World Series director) Dennis Poppe at an NCAA convention. We sat down and had breakfast. When we were done, he said, ‘You’re a member of my team.’ I thought, ‘I’m fixing to go across the country, promoting baseball.’”

While Ellis joined the machine that is the CWS in Omaha, Tom Burnett helped the Southland Conference forge a new path, a key reason the Louisiana Tech graduate was named the Dave Dixon Sports Leadership Award winner.

An “aimless” student at Louisiana Tech, Burnett had an aha moment when he met longtime Tech sports information director Keith Prince.

“It was a lightbulb moment, but instead of popping on, it exploded,” Burnett said. “Within 10 minutes, I knew this was what I wanted to do. Thirty minutes later, I just wanted to be Keith Prince when I grew up.”

Prince’s inability to financially keep Burnett in Ruston was a net positive for a trio of conferences.

Starting with the American South Conference, which later merged with the Sun Belt Conference, Burnett worked his way up to becoming the Southland Conference commissioner in 2003 at age 38. Pushing the envelope, Burnett helped the Southland build its brand through television exposure while balancing that with the needs of student-athletes.

“His genuine concern was for the student-athlete first and foremost,” former Northwestern State President Dr. Chris Maggio said. “Student-athlete welfare was the most important thing for Tom. The most vivid thing to me about Tom was watching his leadership during COVID. Tom was always cognizant of the health and well-being of our student-athletes and how we would test and still be able to have events.”

That personal touch came from Prince, who along with Craig Thompson and Wright Waters made up three of Burnett’s mentors – those who helped him become the first commissioner of a Football Championship Subdivision conference to chair the NCAA Men’s Basketball Committee, which Burnett did in 2022, capping an eventful five-year run on the committee.

“Keith, more than anything, taught me how to treat people, to act around people, to be nice, cordial, work through problems,” Burnett said.

Ardoin, whose versatility and utility earned him the title of “renaissance journalist” from former DSA winner Lyn Rollins, had that in the form of his adoptive parents.

Whether it was covering a game or a city council meeting or teaching in and around his hometown of Opelousas, Ardoin brought a smile to those with whom he interacted.

“You laugh tat him because he’s a grumpy old man or you laugh with him because he has some off-the-wall story about some character he’s covered,” Foote said. “It’s a kick covering games with Bobby.”

The writer-turned-educator-turned-writer again also was able to flip the switch when it came to his students.

“My skills with a computer weren’t very good to start off with,” Ardoin said. “I had a lot of help with my students. They taught me how to use the computer, and to be honest, I stayed around the school system long enough for them to show me just about everything I needed to know about modern journalism. I started off on a typewriter. Some of you may not know what that is.”

What people know about Ardoin, according to Quebedeaux, is if you need the news in St. Landry Parish, you can count on and trust Ardoin.

Within the past decade, Ardoin found his biological parents and family, who also have a bit of journalism in their blood, scoring a victory for nature vs. nurture.

“That’s probably been the most surprising revelation in the past 10 years of my personal life,” Ardoin said. “I spent 73 years wondering who my biological family was and where this writing gene originated. Turns out, it was pretty strong.”

That gene was certainly strong in Ardoin’s fellow DSA winner Ron Higgins.

The son of LSU sports information director Ace Higgins, young Higgins began writing stories at 8 years old while tagging along to the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate in the summers with his father.

Ace Higgins died while Ron was 12 years old – less than two years before young Higgins had his first full byline in the Advocate. That family business spawned a career that included enshrinement in the Tennessee Sportswriters Hall of Fame and a cadre of awards – statewide and nationally.

Higgins’ aura extends well past the words he types in his hunt-and-peck style.

“He is one of the best-dressed writers in the Southeast,” said Teresa M. Walker of the Associated Press in Nashville. “His ability to take and look out for colleagues and other people in the media, bar none he’s at the very top.”

Following in his father’s footsteps was in Higgins’ blood – and in his memories.

“I dove headfirst into it,” he said. “In retrospect, I should have stepped back, but I really wanted to prove myself. I knew since I was 8 that I wanted to be a writer. I loved it. I remember him telling me, be fair with the way you write, be balanced with the way you right. If you write with an opinion, believe in that opinion. Be ethical in dealing with people. I’ve always tried to do that.”

Known for his writing and his second-act career as an extra in movies and television shows, Higgins also is known across the region for his “Mad Dog” nickname – one he bestowed upon himself as a teenager – and for serving as a mentor and sounding board for the next generation of sports journalists.

“Ace Higgins was so symbolic in Louisiana journalism that the LSWA still has an award named for him,” said former DSA winner Dan McDonald. “Ron has stepped forward an awful lot and done some amazing things in his career.”

Fighting back tears, Higgins thanked his wife and children for dealing with the schedule he kept, echoing sentiments heard throughout the night as the inductees handed out plaudits for those at home who did the same.

In the end from half a world away, Cormier summed up what his fellow inductees had to be feeling whether they were born in the Bayou State or simply honed their craft within its borders.

“Boy, it’s good to be a kid from Louisiana,” he said.